Implementation

CGoGN provides an efficient C++ implementation of oriented combinatorial maps. Its main features are combinatorial maps representation, manipulation, traversal and a dynamic attribute mechanism. It is also designed to take advantage of parallel architectures.

Attribute containers

The central data structure used in CGoGN is attribute containers. An attribute container is a set of attributes of arbitrary type that all have the same number of records. Attributes can be dynamically added and removed in an attribute container. An index identifies a tuple of records, one in each attribute of the container. Records can be dynamically added and removed in an attribute container. Removed entries are actually only marked as removed and skipped during the traversals. They are left available for further record additions.

Each attribute is stored as a chunk array, i.e. a set of fixed size arrays. It allows the size of the attribute to grow while leaving all existing elements in place. Chunk size is chosen as a power of 2 so that the arithmetic operations needed to access the record of a given index (division and modulo) are very efficient.

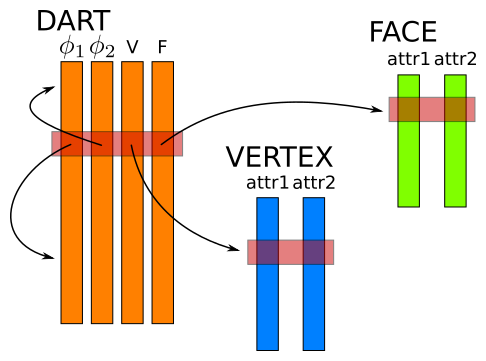

A map in CGoGN is encoded as a set of attribute containers. The only mandatory container is the Dart container. According to the dimension of the map, it stores a variable number of attributes that encode the topological relations φ1, …, φn. Each dart being represented by its index in the Dart container, these attributes store indices of linked darts in the Dart container. For each embedded cell dimension, the Dart container maintains an attribute that stores for each dart the index of its corresponding cell orbit. These indices correspond to entries in a dedicated attribute container. For example, in the map illustrated in Figure 5, Vertex and Face cells are embedded. The Dart container maintains V and F attributes that store the Vertex and Face index of each dart. Obviously, as explained in the embedding section, all the darts of a same orbit share the same index. The Vertex and Face attribute containers store the data associated with each vertex and face cell of the map.

Figure 5: Containers of a 2-dimensional combinatorial map with vertex and face embedding. The dart container stores φ1 and φ2 indices of linked darts and V and F indices of the associated vertices and faces attributes.

Figure 5: Containers of a 2-dimensional combinatorial map with vertex and face embedding. The dart container stores φ1 and φ2 indices of linked darts and V and F indices of the associated vertices and faces attributes.

Basic types

CGoGN defines symbols in the cgogn namespace which will be omitted in the following.

The most basic type defined in CGoGN is Dart which stores an index in the Dart container.

An enumeration of orbits is also defined. These orbits correspond to the different cells that can be defined in a combinatorial map. They are defined as follows:

enum Orbit: uint32

{

DART = 0, // 1d vertex

PHI1, // 1d cycle, 2d face

PHI2, // 2d edge

PHI21, // 2d vertex

PHI1_PHI2, // 2d connected component, 3d volume

PHI1_PHI3, // 3d face

PHI2_PHI3, // 3d edge

PHI21_PHI31, // 3d vertex

PHI1_PHI2_PHI3 // 3d connected component

};

The Cell<Orbit> template class stores a Dart that is publicly available as a dart property. These cell types can actually be seen as orbit-typed Darts.

A combinatorial map is composed of a Dart container and a container for each of the orbits defined in the above enumeration. These containers can be used to store the attributes associated to the cells of each embedded orbit. Containers corresponding to non-embedded orbits will remain unused during the lifetime of the map.

Several map types are defined (one for each dimension). For example, a 2-dimensional combinatorial map can be declared like that: CMap2 map;.

Each map type provides several convenience internal definitions for its cells types. For example a CMap2 provides the following cell types: Vertex, Edge, Face, Volume. These cells are actually defined respectively as: Cell<Orbit::PHI21>, Cell<Orbit::PHI2>, Cell<Orbit::PHI1>, Cell<Orbit::PHI1_PHI2> which correspond to the orbits of these cells in a 2-dimensional map.

A Vertex v contains a Dart and can be thought of as the vertex of v.dart. Any other Dart of the same vertex orbit could equally represent the same cell.

The Mesh abstraction

In a goal of genericity, all informations about a map class are obtain through a traits class cgogn::mesh_traits<Mesh>. Instead of using directly Maps class, all our code will use a template type parameter Mesh. A mesh can of course be a Map but also a object that represent a part of a map (CellFilter, CellCache as explained later), but also any type that could furnish all necessary constants, types and functions definitions.

The introduced complexiy could totally disappear from your code just by adding some type definitions in your class or function. For example :

template <typename Mesh>

void my_algo(const Mesh& m)

{

// cell definition

using Vertex = typename mesh_traits<Mesh>::Vertex;

using Face = typename mesh_traits<Mesh>::Face;

// attribute definition

template <typename T>

using Attribute = typename mesh_traits<Mesh>::Attribute<T>;

Here we need to add the template keyword in each using definition, because we extract something from a template parameter.

In all examples of following sections will use these types definitions.

Attributes

Attributes of any type can be added in a map. The mesh_traits<Mesh>::Attribute<T> template class provides a way to access to the type T values associated to the cells of a map.

Some provided functions allow to add: add_attribute<T,CELL>(mesh,att_name), get get_attribute<T,CELL>(mesh,att_name) or remove remove_attribute<T,CELL>(mesh,att) an attribute.

Functions to add and get return a std::shared_prt<mesh_traits<Mesh>::Attribute<T>>, we encourage you to use the auto C++ keyword for local declaration.

For example, a Vertex attribute storing an integer value on each vertex can be added in a Mesh (that could be a CMap2) like that (using previous type definitions):

using Mesh = CMap2;

using Vertex = typename mesh_traits<Mesh>::Vertex;

Mesh m;

...

auto attr = add_attribute<uint32, Vertex>(m, "attr");

An existing attribute can also be obtained by its name. As the requested attribute may not exist in the map, the validity of the attribute can then be verified:

using Mesh = CMap2;

using Face = typename mesh_traits<Mesh>::Face;

Mesh m;

...

auto area = get_attribute<double, Face>(m, "area");

if (area == nullptr)

{

// there were no Face attribute of this type having this name in the map

}

Attribute values can be traversed globally using the range-based for loop syntax:

for (const double& v : *area)

{

// do something with v

}

Remark: Here we have to used *area because the attribute’s function return a shared_ptr

Given a cell of the map, the value associated to this cell for an attribute can be accessed using the value<T>(Mesh&, Attribute<T>&, Cell) fonction. For example given to a mesh, an face Attribute of double and two Faces f1, f2, we can write:

value<double>(m,area,f1) = 3.4;

double sum = value<double>(m,area,f1) + value<double>(m,area,f2);

Under the hood, this operator will first query the embedding index of the given cell and then access to the value stored at this index in the corresponding Cell attribute container. The embedding index of a cell does not depend on the accessed attribute. Here we have three attributes: Warning when using this code we bypass the checking of the Cell on which attribute is attached.

uint32 findex = index_of(m,f);

(*attr1)[findex] = (*attr2)[findex] + (*attr3)[findex];

Attributes can also easily be removed:

remove_attribute(m,attr);

Global traversals

The cells of the map can be traversed using the foreach_cell method. This method takes a callable that expects a Cell<Orbit> as parameter. It is the type of this parameter that determines the type of the cells that will be traversed by the foreach method. For example, the following code will traverse the vertices of the mesh m and call the given lambda expression on each vertex (we always use type definitions as shown in Mesh abstraction):

foreach_cell( m, [&] (Vertex v)

{

// do something with v

});

No assumption can be made here about the Dart that represents each cell (e.g. v.dart in the previous example) when the processing function is called. Any dart of the same orbit could equally represent the same cell.

Early stop

In order to stop the traversal before all the cells have been processed, the provided callable can return a boolean value. As soon as the callable returns false, the traversal is stopped. In the following example, we are looking for the first encountered vertex for which the Vec3 position value is on the negative side of the x=0 plan. If after the traversal, the declared Vertex is not valid, it means such a vertex has not been found in the map:

// given a mesh m

// given a Vertex looked_up_vertex ()

Vertex looked_up_v;

foreach_cell([&] (m, Vertex v) -> bool

{

if (value<Vec3>(m,position,v)[0] < 0.0)

{

looked_up_v = v;

return false;

}

return true;

});

if (!looked_up_v.is_valid())

{

// no such vertex was found

}

Parallelism

CGoGN can take advantage of parallel architectures to speed-up global traversals. A parallel traversal of the cells can be done using the parallel_foreach_cell function. The processing of the cells of the map will be spread among a number of threads that depends on the detected underlying hardware concurrency. In the following example, the displacement value value of each vertex is added to its position:

// given a mesh m

// given two Attribute<Vec3> position, displacement on VERTEX

parallel_foreach_cell(m, [&] (Vertex v)

{

value(m,position,v) += value(m,displacement,v);

});

It is also possible to aggregate results coming from the parallel processing of several threads. In the following example, the average value of an Edge attribute is computed in parallel. Each thread accumulates the values and number of elements corresponding to the fraction of the mesh that it processes, and then the global result is computed:

// given a Mesh m

// given a attribute of type double on Edge length

std::vector<double> sum_per_thread(thread_pool()->nb_workers(), 0.0);

std::vector<uint32> nb_per_thread(thread_pool()->nb_workers(), 0);

parallel_foreach_cell(m, [&] (Edge e)

{

uint32 thread_index = current_thread_index();

sum_per_thread[thread_index] += length[e];

nb_per_thread[thread_index]++;

});

double sum = 0.0;

for (double d : sum_per_thread)

sum += d;

uint32 nb = 0;

for (uint32 n : nb_per_thread)

nb += n;

double average = sum / double(nb);

Note that early stop is not available when doing parallel traversals.

Customized traversal

In their simplest form, the foreach_cell and the parallel_foreach_cell methods process all the cells of the mesh. But they can also be called with other kinds of parameters: a CellFilter

CellFilter

A CellFilter encaspsule a Mesh object by adding a boolean functions on each type of cell you want to filer. Once CellFilter is created, it can be used as a normal mesh in a foreach.

In the following example, the function will print only the faces for which the area is above a given threshold:

void print_faces(const CMap2& m, const Attribute<double>& area, double threshold)

{

CellFilter<CMap2> cfm(m);

cfm.set_filter<Face>([&](Face f) -> bool {return (value<double>(cfm, area, f) > thresold; });

foreach_cell(cfm, [&](Face f) -> bool {

std::cout << f << std::endl;

return true;

});

}

A same CellFilter object can of course define one filter for each of its type of cell (for example Vertex, Edge, Face for CMap2)

CellCache

With the previous Masks, even when using a filtering function, all the cells of the map are always traversed and the filtering function is evaluated on-the-fly for each cell in order to decide if the processing function should be called on it or not. This can be great in a dynamic environment where the set of filtered cells changes regularly. But if the set of filtered cells is stable, and moreover if this set is small w.r.t. the number of cells of the map, a more efficient solution can be proposed.

A CellCache can store a set of cells for each type of cell. These sets will be directly traversed by the foreach_cell or parallel_foreach_cell method.

The most easy way to populate a cache is to use the build method build<CellType> which builds the set of the mentioned cell type, using the filtering bool function parameter.

There is also an add<CELL> method for individual insertion, and a global clear() method.

In the following example, all the degree 5 vertices are put into a cache which is then used in a traversal that is efficient and restricted to those vertices:

// given a CMap2 map

CellCache cache(map);

cache.build<Vertex>([&] (Vertex v)

{

return degree(map,v) == 5;

});

foreach_cell(cache, [&] (Vertex v)

{ /* do something with v */

});

Note that if a new cell that satisifies the filter is inserted into the map, it will not be part of a cache that has already been built.

Note also that if any cell stored in the cache is deleted from the map, the cache is invalid and any subsequent traversal with this cache will fail.

The “snapshot” property of the CellCache can be particularly exploited within algorithms that insert new cells during the traversal of the map. Indeed, without such a mechanism, the newly inserted cells could also be traversed resulting in a possible infinite loop. In the following example, all the edges of the map are cut by inserting a new vertex. Only the edges that existed at the moment the cache was built are considered:

// given a CMap2 map

CellCache cache(m);

cache.build<Edge>();

foreach_cell(cache, [&] (Edge e) { cut_edge(m,e); });

Local traversals

All the incidence and adjacency relations between cells are encoded within a combinatorial map. We first give an intuitive definition of what we mean by incidence and adjacency relations and then show how to make these neighborhood traversals in CGoGN.

Incidence

Let C1 and C2 be two cells of different dimensions with dim(C1) > dim(C2). C2 is said to be incident to C1 if it belongs to the sub-tree under C1 in the incidence graph (for example, the four vertices and the four edges that bound a quad face in a 2D mesh are said to be incident to this face). C1 is said to be incident to C2 if it is part of the ancestors of C2 in the incidence graph (for example, the six edges and the six faces around a vertex in a regular 2D triangle mesh are said to be incident to this vertex).

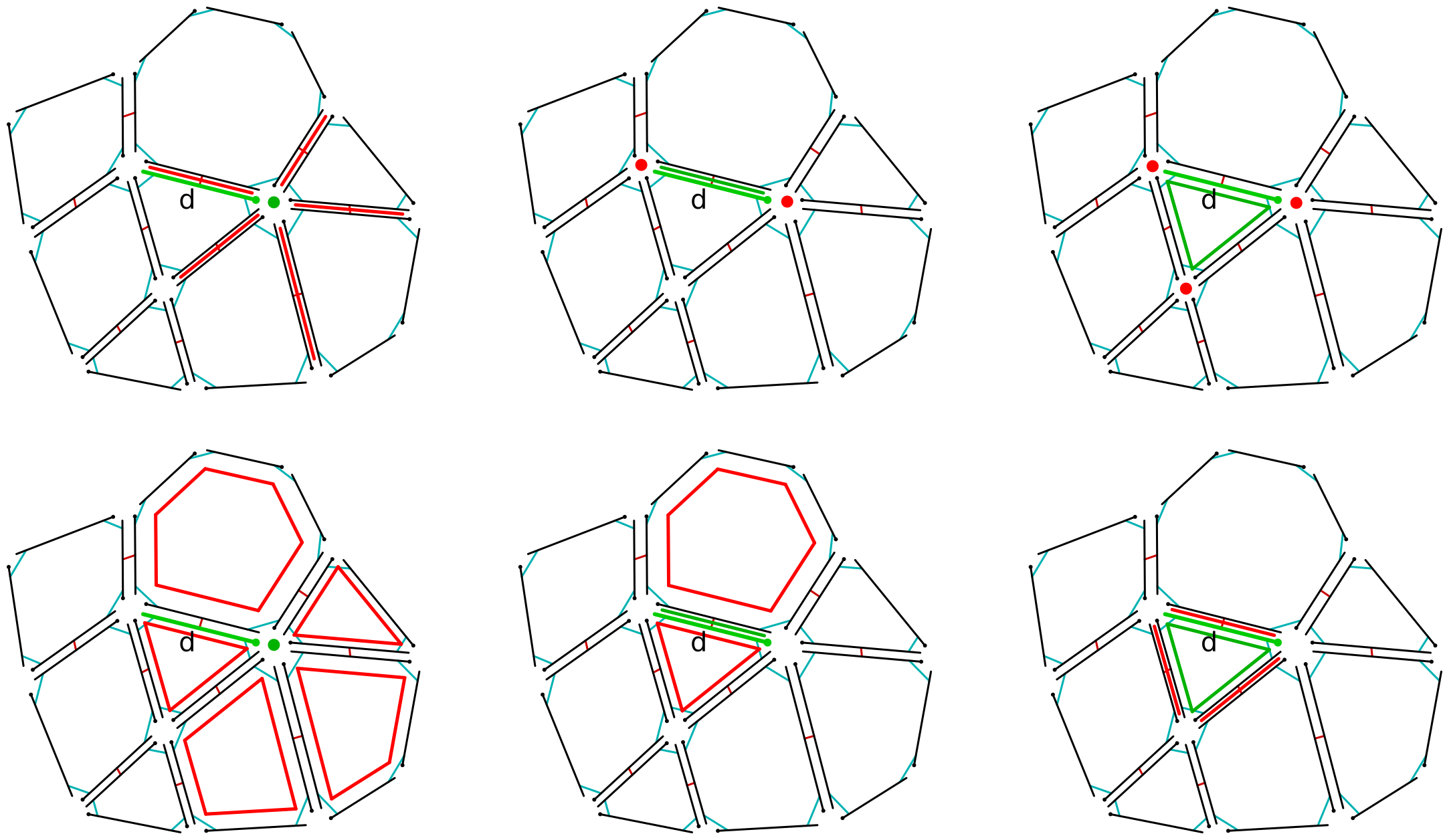

The following Figure 6 illustrates the incident cells in a 2-dimensional map and Figure 7 illustrates some of the incident cells in a 3-dimensional map.

Figure 6: Incident cells traversals in a 2-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and incident cells are drawn in red. Top-left: incident edges of a vertex; Bottom-left: incident faces of a vertex; Top-middle: incident vertices of an edge; Bottom-middle: incident faces of an edge; Top-right: incident vertices of a face; Bottom-right: incident edges of a face.

Figure 6: Incident cells traversals in a 2-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and incident cells are drawn in red. Top-left: incident edges of a vertex; Bottom-left: incident faces of a vertex; Top-middle: incident vertices of an edge; Bottom-middle: incident faces of an edge; Top-right: incident vertices of a face; Bottom-right: incident edges of a face.

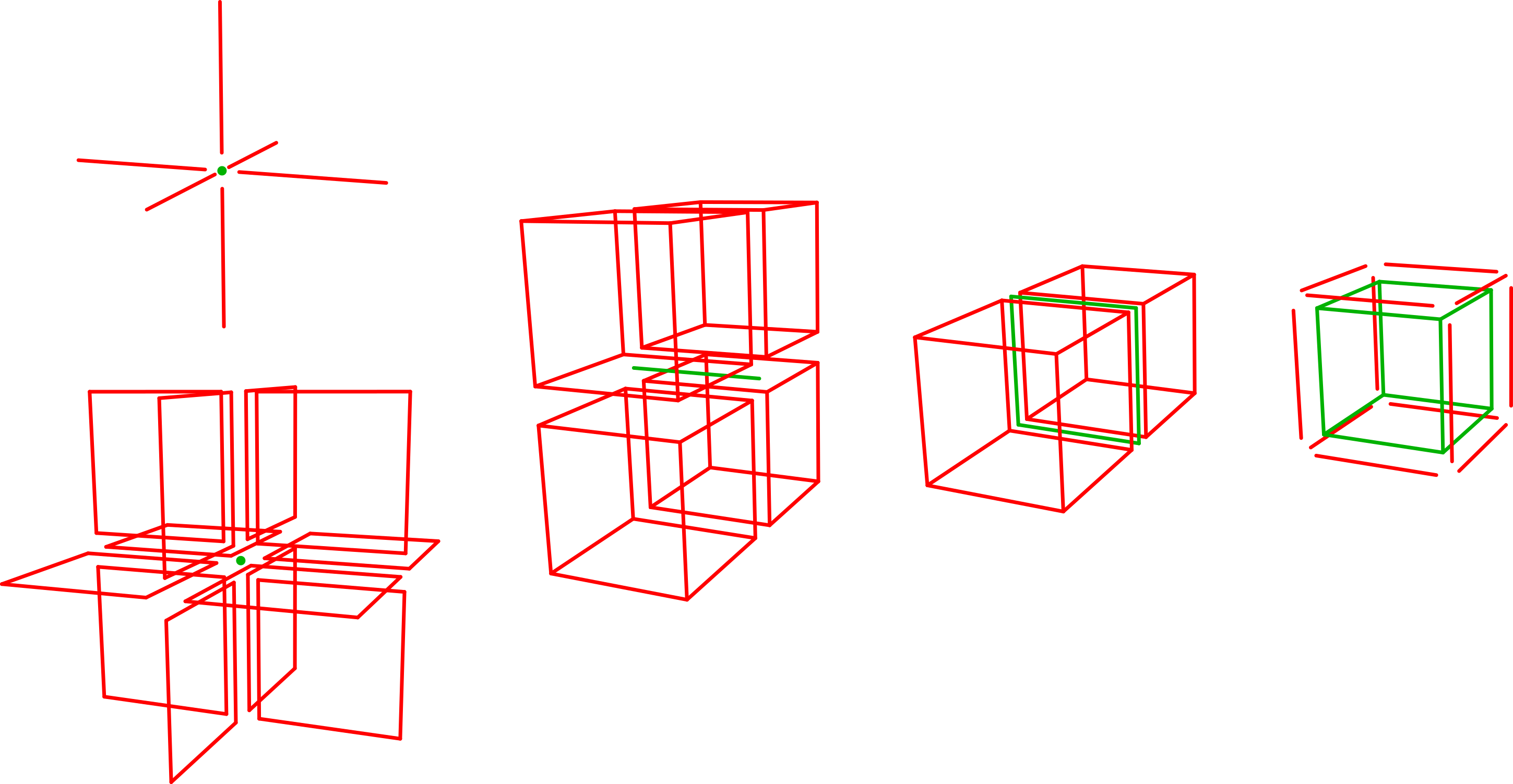

Figure 7: Some of the incident cells traversals in a 3-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and incident cells are drawn in red. From left to right: incident edges of a vertex and incident faces of a vertex; incident volumes of an edge; incident volumes of a face; incident edges of a volume.

Figure 7: Some of the incident cells traversals in a 3-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and incident cells are drawn in red. From left to right: incident edges of a vertex and incident faces of a vertex; incident volumes of an edge; incident volumes of a face; incident edges of a volume.

Adjacency

Two cells of equal dimension C1 and C2 are said to be adjacent if they share a common incident cell. For example: two vertices are said to be adjacent through an edge if they are both incident to a same edge; two faces are said to be adjacent through a vertex if they are both incident to a same vertex.

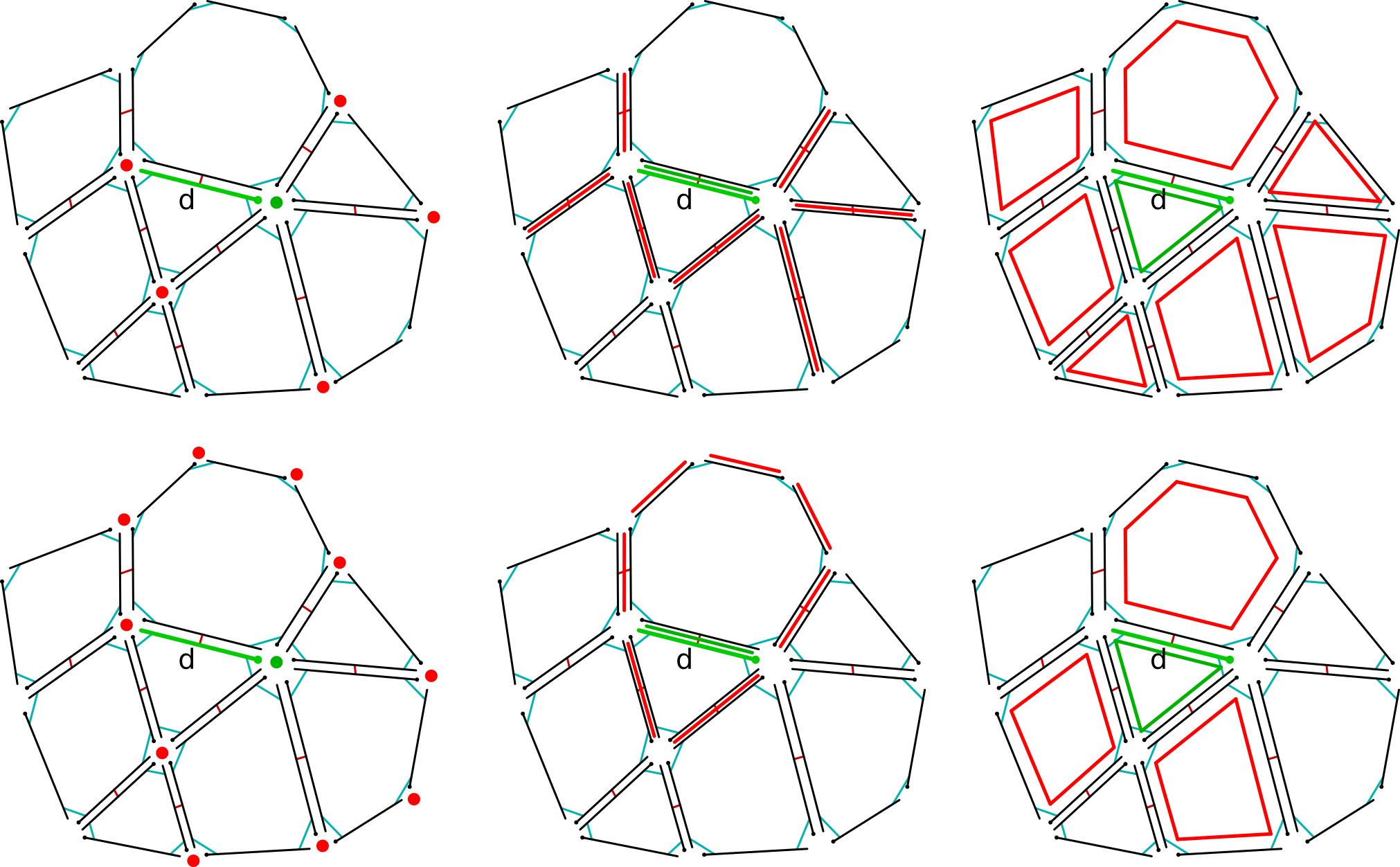

Figure 8: Adjacent cells traversals in a 2-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and adjacent cells are drawn in red. Top-left: adjacent vertices through an edge; Bottom-left: adjacent vertices through a face; Top-middle: adjacent edges through a vertex; Bottom-middle: adjacent edges through a face; Top-right: adjacent faces through a vertex; Bottom-right: adjacent faces through an edge.

Figure 8: Adjacent cells traversals in a 2-dimensional map. Central cell is drawn in green and adjacent cells are drawn in red. Top-left: adjacent vertices through an edge; Bottom-left: adjacent vertices through a face; Top-middle: adjacent edges through a vertex; Bottom-middle: adjacent edges through a face; Top-right: adjacent faces through a vertex; Bottom-right: adjacent faces through an edge.

Local traversal methods

CGoGN provides methods to traverse all these local neighborhoods. These methods all work in the same way: the callable given as second parameter is called on all the requested incident or adjacent cells of the cell given as first parameter. If this callable returns a boolean value, the traversal is stopped as soon as this value is false.

In a 2-dimensional map, the local neighborhood traversal functions are the following:

foreach_incident_edge(Mesh, Vertex, [] (Edge) {})foreach_incident_face(Mesh, Vertex, [] (Face) {})foreach_adjacent_vertex_through_edge(Mesh, Vertex, [] (Vertex) {})foreach_adjacent_vertex_through_face(Mesh, Vertex, [] (Vertex) {})foreach_incident_vertex(Mesh, Edge, [] (Vertex) {})foreach_incident_face(Mesh, Edge, [] (Face) {})foreach_incident_vertex(Mesh, Face, [] (Vertex) {})foreach_incident_edge(Mesh, Face, [] (Edge) {})foreach_incident_vertex(Mesh, Volume, [] (Vertex) {})foreach_incident_edge(Mesh, Volume, [] (Edge) {})foreach_incident_face(Mesh, Volume, [] (Face) {})

The following example illustrates a function that computes the average of vertex attribute values over the vertices incident to a face in a 2-dimensional map:

template <typename T>

T average(const Mesh& map, Face f, const Attribute<T>& attribute)

{

T result(0);

uint32 nbv = 0;

foreach_incident_vertex(m, f, [&] (Vertex v)

{

result += attribute[v];

++nbv;

});

return result / nbv;

}

Of course here the type T must be numerical and provide operators += and /.

Given that all the equivalent neighborhood traversal functions are also defined in 3-dimensional maps, the previous function can be easily generalized to the computation of the average of vertex attribute values over the vertices incident to a n-cell in a n-dimensional map:

template <typename T, typename CellType, typename MESH>

T average(const MESH& m, CellType c, const typename Attribute<T>& attribute)

{

T result(0);

uint32 nbv = 0;

foreach_incident_vertex(m, c, [&] (typename MESH::Vertex v)

{

result += value(m,attribute,v);

++nbv;

});

return result / nbv;

}

Properties

Several functions can provide some properties about the map or the cells.

- nb_cells <!– - nb_boundaries

- same_cell –>

- degree

- codegree

- is_incident_to_boundary

Operators

Each of the following operator is provided only if the Mesh type that allows it. For example the flip_edge operator has sense only on surfacic Mesh like CMap2

- Vertex cut_edge(Mesh,Edge)

- Vertex collapse_edge(Mesh,Edge)

- void flip_edge(Mesh,Edge)

- void merge_incident_faces(Mesh,Edge)

- Edge cutFace(Mesh)

- Face cut_volume(Mesh,std::vector

)

Warning: Operators do not fill or compute any attribute even the position. You can add the false as last parameter on each function if you want apply pure topological operators (embedding indices not updated)

Creation

- Face add_face(Mesh, uint32)

- Volume add_prism(Mesh, uint32)

- Volume add_pyramid(Mesh, uint32) Warning: Operators do not fill or compute any attribute even the position. You can add the false as last parameter on each function if you want apply pure topological operators (embedding indices not updated)

Marking

Ther are some classic problems like:

- how be sure to not traverse twice the same cell.

- how do no traverse the cells that I am currently adding in the mesh

To avoid these problems we use Markers. CellMarkers for cells and DartMarker for low-level usage on maps

CellMarker

A CellMarker if an object that allow to mark/unmark cells of a choosen type (second template parameter), to test if the cell is marked, and clean

// creation (here for vertices)

CellMarker<Mesh,Vertex> cm{m};

// test if a cell v is maked

if (!cm.is_marked(v))

// mark the cell

cm.mark(v)

// unmark the cell

cm.unmark(v);

// possible to unmark all marked cell (call implicitly on destruction of CellMarker)

cm.unmark_all();

You can use as many markers as you want, like color markers on a white table.

A CellMarker use an attribute for storing its marking data. That could be totally unoptimal if you know that your are marking very few cells, because the cost of cleanning of the marker is

linked to the size of the mesh. For these cases it is advise to use a CellMarkerStore. The interface is the same, but is store the marked cells are also stored in a vector, that allow to clean the marker very quickly. Warning unmark if here more costly than mark (find algorithm in a vector). You have also access to the vector of cells

Use only CellMarkerStore if:

- you mark few cells (compare to number of cells of the mesh)

- you do a lot of mark and unmarkall but very few unmark (individual cells cells)

- you do a lot unmarkall

- you do very few individual unmark